Is contextualised admission the answer to the access challenge?

Anna Mountford-Zimdars | Senior Lecturer in Higher Education | King’s College London

Abstract

This article reviews the idea of contextualizing applicants to higher education in order to widen access. First, the meaning of contextualized admissions is discussed before laying out the rationale for contextualizing applicants and the beneficiaries of the policy. The final sections discuss key critiques of contextualized admission and conclude by arguing that contextualized admission does go some way to addressing the access challenge. To fully realise its potential as a policy intervention though, it is most helpfully part of integrated support for students throughout university and is mindful of the role of universities in wider society to create more equal progression trajectories for young people from a range of backgrounds.

Introduction

Fair access to higher education for different social groups is a key challenge and is part of the wider focus in the UK on the contribution of higher education to social mobility and labour market entry and returns. There are differential transition rates into higher education for disadvantaged groups across all industrialised and emerging economies. The primary barriers for some social groups not transitioning into higher education concern the unequal distribution of opportunities to complete and attain highly in secondary education; the ability and willingness to pay for education; the geographic accessibility of higher education; differences in cultural and social capitals to navigate educational systems and curricula; differences in access to information, advice, and guidance as well as embedded familiar, cultural and social expectations. It is therefore right that public policies to facilitate greater equality in progression into and through higher education should primarily focus on addressing and overcoming these key barriers.

However, secondary challenges to equality of participation in higher education are that some students do not apply to the most prestigious universities they might gain admission to or that they are not admitted once they have applied. This article explores whether for those applicants contextualised admission (CA) might be able to increase transition rates into higher education.

We first consider the challenges CA seeks to address and discusses the rationale for using CA. There is a description of how CA works in practice as well as a discussion of the criticisms of CA. We root our discussion primarily in a UK perspective but draw on some examples from other countries to illustrate that alternative approaches to increasing enrolment of under-represented groups are available. We also consider which issues CA is equipped to address and which ones are beyond its scope.

In conclusion the article argues that CA can enhance higher education access, in particular to selective higher education, for some disadvantaged student groups. To realise its full potential as an intervention, however, CA needs to be part of an integrated approach that encompasses support and outreach prior to higher education and continues throughout the student lifecycle or student progression within higher education into further study and employment.

The meaning of contextual admissions

In stratified hierarchical university systems like the UK, some universities and courses admit only a fraction of their applicants. A key driver in admissions’ decisions is applicants’ previous academic attainment. This imperfect measure is key to unlocking the proverbial university gate and subsequent graduate labour market opportunities for which the prestige marker of the university attended is important. However, there is controversy as to the extent to which prior ability can measure potential rather than only ability. The basic idea of CA then is that it enables higher education institutions to consider other factors than prior grades as part of their admissions process and to admit applicants with the potential to succeed despite perhaps slightly lower grades than some other applicants.

There are three key features to UK contextualised admission: Contextual data, contextual information and contextual outreach. Contextual data are either taken from the actual application or derived from linking information in the application to other sources of information. Disadvantaged applicants are then ‘flagged’ for particular consideration. Contextual information is available through information about applicants’ background from, for example, their personal statement, school references and sometimes also additional admissions questionnaires or local knowledge of schools and colleges. A third stream is contextualisation through participation in outreach activities. Here, the targeting for participation in itself signals that an applicant was identified as disadvantaged before applying to higher education as they met the criteria for inclusion in targeted outreach (Bridger et al. 2012 p.15).

Contextualised admission in the UK means contextualising primarily the academic attainment of an applicant for HE admission. This helps selectors to evaluate whether applicants’ prior attainment reflects their true potential for academic success in higher education. This contrasts with other countries like for example, the US or Germany, where other contextual factors like having overcome adversity (US) or disability and caring responsibility (Germany) might be considered.

While the idea of CA has potential merits for a wide range of universities and colleges ranging from the highly selective with ‘traditional’ qualifications to those seeking to expand their pool of students by giving credit to a wider range of experiences, the CA movement in the UK was initially associated with selective universities in a context where demand for places vastly exceeds available places for study. Recently, a wider range of providers have adopted the policy and CA might be used for e.g. looking for students without traditional entry qualifications (SPA 2015).

The idea of contextualising the prior academic attainment of applicants to higher education is not in itself new and can be traced back to at least the 1960s and 1970s. For example, an academic at the University of Oxford described in 2005 how contextual considerations had been taken into account for decades:

“I remember years ago – in the early 70s, the… Ancient Philosophy tutor…used to say ‘Oh, yes, but for somebody from that, comprehensive, or secondary [school], or whatever it was then – this is a very good performance!’ – So, I think Oxford has always looked at that sort of thing. The question now is that given the data availability should we be using it more formally?” (Zimdars, 2007, p. 234). The term contextualised admissions, however, is a much more recent term that has only really taken off in England in the 21st century. Prominent in mainstreaming the term was the recommendation in the Schwartz Report (2004) that contextual admissions should be used as part of fair admissions. Targets agreed between universities and the Office for Fair Access to achieve a higher representation of disadvantaged students in higher education have further driven the contextual admission agenda.

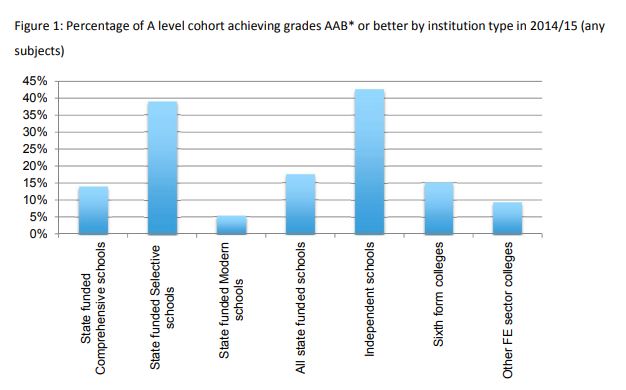

This is because of the continued relationship between attainment and socio-economic background, meaning that the most advantaged students, however measured, will usually have higher grades than their less advantaged peers. Table 1 shows the differences in the English school-leaving examination, the A levels, and differences by the type of secondary school attended for 2013/14, showing that those in feepaying schools and academically selected state schools have the highest attainment. Other analysis have found how the ‘gap’ in progression to higher education at age 19 between pupils who aged 15 had Free School Meal eligibility status and other state school pupils was 18 percentage points (BIS, 2011). The estimated progression rate for state school and college pupils to the most selective Higher Education Institutions was 26% in 2008/09, compared to 62% for fee-paying school and college pupils (BIS, 2011). Such findings suggest that attainment captures socio-economic differences between communities as well as the effects of qualitative differences between schools.

*A level or applied single/double award A level. Modern schools and comprehensives admit pupils of any ability. Secondary modern schools will have grammar schools in their area which admit most local high ability pupils and may therefore may a different intake compared to comprehensive schools which are not in grammar school areas. Source: Department for Education, Statistical First Release 03/2015 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/a-level-and-otherlevel-3-results-2013-to-2014-revised

Contextualised admission is an attempt to make sure some relatively high achieving students who may be educationally and socio-economically at a disadvantage to other applicants remain eligible for places at selective universities.

The first university to systematically adopt an official contextualised admissions policy was the University of Edinburgh in 2004 (University of Edinburgh, 2015, p. 4). The use has since spread across the Russell Group1 and other HE providers. The development of contextual admissions policies in individual universities has been supported through central resources, especially the organization Supporting Professionalism in Admissions (SPA, established 2006) and the national central admissions service used by all full-time applicants for UK undergraduate degrees, UCAS. SPA and UCAS developed a ‘basket of data’ that provides a range of additional background information such as area information about applicants to higher education (SPA 2013). There have now been national reports and research into contextualised admission

(Bridger et al. 2012; Moore et al. 2013) and contextual admission is referenced in recent policy documents (QAA 2013; OFFA 2013, Scottish Funding Council Guidance on Outcome Agreements 2013). Overall, the UK experience shows that sourcing, accessing and using data on the educational and socioeconomic background of individual higher education applicants greatly helps the practical development of contextual admissions policies.

Why use Contextualised Admissions?

A range of conceptual rationales and arguments can be marshalled in support of CA. These can be divided into social justice, diversity, civicness, economic and social mobility, and practical rationales. These are now discussed in turn.

For some supporters of HaCA, the primary driver is rooted in social justice considerations and that contextualising applicants is the right thing to do in itself (Weber 1922/2013). For example, the Universities of Edinburgh and Manchester, both early adopters and leaders in the contextualised admission landscape, are comfortable describing their contextualised admissions policy in detail on their websites and with reference to social justice considerations. However, not all universities are equally comfortable using this narrative in their description of contextualised admissions policies.

A related argument concerns how holistic admission allows for admitting a more diverse student body compared with attainment-only based admissions system. This enables a diverse learning environment thus preparing students for being effective members of diverse societies. This argument is not generally used in the UK although it is frequently used to support holistic admission in the US context where civic engagement achievements and potential for ‘social returns’ also feature (see e.g. Bowen and Bok 2000).

The idea of social returns leads into a more economic argument that not admitting students into (elite) higher education who have particular potential to contribute to university life and later on, to society, employment, and to the economy, is a waste of talent and human resources. Closely entwined with the argument of wasting talent is the social mobility argument.

Economic and social mobility based arguments enjoy cross-party political support in the UK and are thus the dominant way of framing the use of contextualised admission in British public discourses. Crucial senior support for this agenda came from the Conservative Minister of State for Universities and Science (2010-2014), David Willetts; Alan Milburn’s Social Mobility and Child Poverty commission and the 2015 Green Paper. Indeed, some universities and individual advocates for contextual admission find it advantageous that the social mobility and economic argument can bypass more politically divisive discussions regarding fairness, life-chances, and the structural roots of inequality. For example, a university leader explained that while he personally had a more left-leaning world view and was passionate about tackling social inequities contextual data tried to address, this was “politically the most contentious thing…on my governing body it’s a very difficult issue”. (Mountford-Zimdars 2016). It can thus be crucial for someone in this position to demonstrate the instrumentally derived value or economic and social mobility reasoning for using contextual data. There is also research empirically supporting the argument that those admitted to Russell Group institutions from schools where the average attainment was below the national average attain more highly at university than those admitted with the same grades from schools where all students attain highly (HEFCE 2003, Ogg et al. 2009, Hoare and Johnston 2011, Taylor et al. 2013, Lasselle 2014; but see Parks 2011, Partington 2011, Chetwynd 2011). These findings are then used as an argument for considering those with good, but not excellent grades from less good schools to have equipotential for high achievement at university compared with high attaining students from schools that perform higher than the national average ² .

Contextual admission then uses a discourse of selecting the best students and finding academic excellence in context in order to achieve the best outcomes. By having a professional admissions process and a transparent and systematic contextual admission approach to evaluating applicants, a greater pool of talented students from disadvantaged backgrounds is expected to apply to selective universities and thus a greater number are expected to be admitted and to gain graduate employment thus advancing social mobility.

Finally, there is a practice-based rationale for using CA. UK Universities engage in a range of outreach activities that encourage and support disadvantaged students to consider and apply to selective higher education institutions. A challenge in outreach work has been that it is not always linked to university admission. This can create a situation where plenty of effort and resources go into working with children and adolescents to make them aware of higher education and to support them in applying to elite universities. However, when these young people are ultimately not admitted to their preferred university, disappointment sets in and some argue that the aim of outreach is not realised. By giving special consideration to students who have already participated in outreach activities, CA then offers a way to allow institutions to translate outreach efforts into a higher chance of admission for participating students. Such outreach students, in turn, are more likely to take up their offer for a place and enjoy higher retention in higher education than similar applicants who were not part of outreach schemes (Bridger et al. 2012).

In sum, key drivers for contextual admission in the UK are national policy drivers linked to social justice and universities’ corporate responsibility, but also practical requirements related to monitoring requirements and targets in widening participation such as the percentage of state school students.

Who benefits from CA?

Overall, there is an unfortunate paucity of robust evaluations on who benefits from CA in the UK, but the evidence that does exists suggests that institutions take into account geographic considerations such as being from an area with poor progression into HE or deprivation, personal factors such as having been in foster-care, and participation in outreach (Moore et al. 2013). Flagging applicants for special consideration through CA is usually based on a framework of considerations that includes social background, educational, geographic / geodemographic, and personal circumstances. Contextualising attainment by school type results in “adjustment sponsorship” (Mountford-Zimdars 2015) or enhanced admissions chances for those who went to state as opposed to private schools.

The following example shows how CA works in practice:

Shamina is 17 and has always been in state sector schooling. Most of the students in her school do not continue their

education into university. She is a very high attaining student within her school context. Because her school and the area where she lives have low progression to higher education, she has applied and been selected to participate in an outreach scheme run by a Russell Group university. She has participated in various workshops and a summer school and received help with her university application. She has now applied to a Russell Group university as well as four other universities to study Economics and Management.

The admission office at the Russell Group University has a contextualised admissions policy. The policy considers educational, geo-demographic and personal factors. The consideration of educational factors mean that the admission office looks at the school where Shamina took her examinations at age 16 (GCSEs) at age 17 (AS levels) and age 18 (A-levels). They find that national data shows the school’s performance for both examinations has been below the national average for the past three years. Shamina’s application is flagged to indicate that her excellent grades were achieved in a below average achieving school, thus highlighting her particular achievement to the selectors – Shamina is a big fish in a small pond. The selector then looks at Shamina’s home-postcode against a national classification of wealth such as an Index of Deprivation or against a classification that shows how many young people from the area typically participate in higher education. The postcode data indicates that Shamina lives in an area with high disadvantage. In the personal circumstances section, the admissions officer flags that Shamina has participated in an outreach programme run by the University. The selector does not consider Shamina’s race, her parents’ occupations – indeed this information is not available at the point of selection – , gender or whether the school she attended was a state or private school. The admissions officer notes there are three or more factors that may indicate disadvantage, triangulation of information is important when using proxies for individual disadvantage.

The admissions office now offers a place for study to Shamina that requires her to achieve slightly lower entry grades than peers who applied without triggering contextual admissions flags. Shamina will still have to meet the minimum academic requirements that the university deems necessary to successfully graduate in Economics and Management, but she does not have to meet the very highest grades one could possibly achieve in school-leaving examinations. The University will also now consider Shamina for a needs’ based bursary to help towards the cost of studying at university and other support that could be provided to aid her transition into higher education.

The example of how an admission would be considered under a contextualised admissions policy is loosely based on the guidelines for the use of contextual data at the University of Edinburgh (2015). Edinburgh has found that the use of contextual flagging has “Alongside innovative and sector-leading outreach projects such as Pathways to the Professions, and needs-based bursaries, the University’s use of contextual data has enabled a gradual increase in the diversity of educational and socio-economic backgrounds from which students come to Edinburgh.” (p. 5).

Overall, there is no single way in which universities in the UK use contextual admission, just as there is no universal way of making admissions decisions. In some universities, full-time admissions professionals assess applications and make admissions decisions on individual applicants (to criteria agreed by academic teams) whereas it is academic faculty who assess applications and make decisions in an – albeit shrinking – minority of other universities (SPA 2014), some universities and subjects use admissions interviews and/or additional tests whereas many universities and subjects make decisions based solely on the application data they receive through UCAS. Some universities use contextual data to help with shortlisting for admissions interview, others use it to give additional consideration to applicants and some use contextual data as the basis for making differentiated offers to applicants for admission.

Most institutions use a range of different contextual indicators, commonly related to educational background, socio-geographic context, and personal consideration like having been in care or a refugee. Having the application flagged can mean special consideration, being invited for interviews (where applicable) when an applicant would not be otherwise and being offered a place for study with lower grades than more advantaged applicants. A more detailed discussion of different approaches to contextual admission is provided in Moore et al. 2013 and a comparative overview of US and English admission is provided in Mountford-Zimdars 2016.

On aggregate, many universities find that their overall representation of disadvantaged students has increased year-on-year since introducing contextual admissions flags. It remains a research challenge, however, to evaluate how many individual students have been admitted through contextual admission who may not have been admitted without it in light of the complex factors impacting on admissions and transition to higher education.

Critique of contextualised admission

Perhaps the greatest criticism levied of CA is that it could be used as a smokescreen to hide the continued association between social origin and grades in school (Machin 2006). The sociologist Turner has described that this link means liberal democracies are then merely ‘surface’ rather than ‘deep’ democracies (Turner 1966). By allowing some flexibility in admission – especially for elite universities – CA may confer legitimacy to a system of elite and non-elite institutions and focus attention away from the fact that most disadvantaged students participate in the lower prestige forms of education in any stratified higher education system (e.g. Brint and Karabel 1989, Croxford and Raffe 2013, Chowdry et al. 2013). By giving exceptional adolescents who have succeeded against the odds opportunities for elite higher education, CA also risks creaming off the few and creating an illusion of social mobility for the many, thus potentially again reinforcing structural inequalities and further legitimising such inequalities in the process. The counterargument is that not doing anything at all will certainly not enhance the situation.

A related criticism is that CA – especially at selective universities – may not be ‘widening’ participation to those who would not participate in higher education otherwise. Instead, there is an element of ‘shifting’ participation meaning that those who are admitted through CA at highly selective universities would have been very likely to secure a place at alternative institutions in higher education. The argument here is that CA at selective universities may not make the difference between whether or not someone participates in higher education per se but only where they participate. A counter-argument is that diversifying the student body at elite higher education could be considered a good thing in itself and with more individual social mobility and perhaps societal benefits: because of differential returns to different types of higher education, increasing access to elite institutions matters.

Another criticism is that research and discourses on CA – perhaps surprisingly – do not generally consider the effect of not being admitted into selective higher education on disadvantaged students who were supported and encouraged to apply and who then miss out on a place for their preferred university.

Criticism of CA has also come from within the practitioner community in admission and outreach and often concerns disagreement over the implications of data use for offer making or concern regarding the flagging of some but not other groups. For example, the issue of taking into account whether or not someone has successfully completed an outreach programme can be controversial. On the one hand, it does not seem right to raise aspirations among those targeted for outreach to then disappoint them in the admissions process. On the other hand, one could argue that those who participate in outreach already enjoy enhanced support and other applicants who may have been eligible to participate in outreach but did not have the opportunity to, are then extra-disadvantaged. An example of disagreement was observed in a training meeting for admissions tutors where one selector argued: “Why should I give an advantage to someone from a bad school from inner London? How is that more worthy than considering the educational disadvantage experienced by a rural white British boy from the North of England?” (Zimdars, 2007, p. 235 – incidentally, this group has since moved into public consciousness). US holistic admissions approaches are more flexible with regards to the complex individual circumstances than data-driven contextual flagging used in the UK. The blunter instrument of flagging, however, allows for relatively low cost implementation and can provide some consistency and transparency.

There is also a criticism that contextualised admission does

not go far enough and that genuinely taking into account prior differences in

opportunities, means changing the university experience and curricula. King’s

College London was the first university in 2000 to develop an ‘Extended

medicine’ programme where not only admission but the entire first three years

of the medical degree programme are contextualised (King’s College 2015).

Students admitted to the programme enjoy additional study support and a lighter

work-load as the first three years of a medical degree are taught over four

years. This education model has recently been widened to an enhanced support

dentistry programme at King’s College.

Discussion, summary, conclusion

To summarise, CA is a way to acknowledge that treating all applicants the same

may not provide equality of opportunity in university admission. CA

contextualizes applicants’ academic attainment and personal circumstances with

a view to increase participation in – especially selective – higher education

of previously under-represented groups. CA improve in some marginal way

equality of access for beneficiaries of the policy.

Arguably, CA is only relevant in marketised HE systems with elite institutions and selective admissions based on prior attainment. It is therefore perhaps not surprising that interest in the use of HaCA comes from other countries with stratified higher education systems. Ireland has recently developed its first pilot project to complement grade-based admission with contextual considerations (Geoghegan 2014) and there is interest in Australia to think about CA.

In other countries, there is arguably less of a need for such policies as the higher education systems are more accessible in the way they are structure. For example, in the German higher education model students have the right to participate in higher education as long as they pass their school-leaving examination Abitur. Few subjects have enrollment restrictions and there are no tuition fees. There is thus a general ‘open access’ policy to higher education for the vast majority of students. Extra advantages in enrolment are given to students who need to live locally due to family commitment or disability and students who have taken time out since school. The Danish and Scandinavian approach is to pay all students to participate in higher education with the stipend eliminating family economic resources as a predictor of who participates (e.g. Thomsen 2012).

Even when countries face situations where there are more potentially eligible students than there are higher education places, CA is not the only possible response. For example, the Dutch medical lottery gives a weighted chance of being admitted to study medicine for students within different bandings of school leaving grades (Stone 2015). Reasoning, good and bad, is thus eliminated from decisions. Instead of context the CA context-conscious approach, lotteries are context blind.

Who is disadvantaged is arguably an essentially contested concept (Gallie 1956). There can be crossnational differences in which groups or individuals are considered worthy of special or additional consideration. Where CA is used, there are vivid debates as to the virtue of extending the logic of CA to less selective institutions. Here, the objective would be to find students whose prior qualifications might not easily make them traditional applicants for higher education, but whose experiences show potential to stay and succeed in higher education. Integrated support during the application period and during higher education for those admitted with non-traditional qualifications would have to be an integral part for the success of such policies.

Different approaches to taking into account the context of applicants to higher education, inevitably, have different advantages and drawbacks. Open access policies are, for example, fairer at the point of entry in allowing everyone who wishes to do so to enrol. However, when there is a high drop-out as it occurs in Germany, some UK higher education providers or Community Colleges in the US, such access opportunities do not lead to enhanced outcomes for those benefitting from them. At the same time, contextual admission tends to apply at the margins and is essentially a ‘top down’ approach based on the criteria decided institutionally so cannot come close to overcoming the structural barriers to higher education facing the most marginalized groups, unlike the ‘bottom-up’ open access approaches in the other countries which gives everyone a chance in higher education.

This article posed the question whether CA is the answer to the widening access challenge. The answer here has to be that, even when this is used as the most appropriate way to take into account the different contexts of applicants, it can only be a partial answer to the access challenge although CA is well placed to be an answer to the fair admissions challenge. For CA to work, it needs to be part of an integrated student life-cyle or progression approach that not only allows students to come through the gates of a university but that facilitates students’ success within higher education.

Retention rates are high – in the high 90 percent – for the most selective universities that use CA, whether it be Oxford in the UK or Harvard in the US. However, some differences in terms of attainment within universities as well as labour market outcomes can remain. The test for whether CA has ultimately worked is then about success within and after higher education. To conclude, CA and other admissions policies can only ever be part of the answer to the access challenge. To create a more socially just higher education system, an integrated approach is needed that joins up outreach and early year works with admission and support at university and into employment or further study. As part of such an integrated approach, CA can play a crucial part in making educational journeys that little bit fairer. At the same time, while working towards continuously enhancing the possibilities of CA, practitioners and scholars need to be mindful that CA is an interim measure that would be obsolete if societies succeeded in creating greater opportunities for all regardless of the accident of educational, geographic and personal contexts.

__________________________________

1 The Russell Group is a group of 24 universities that focuses on research excellence and teaching. The Russell Group has a strong focus on postgraduate as well as undergraduate education and award the majority of doctorates in the UK.

__________________________________

2 The way schooling is operationalised in different research projects can vary. Some previous academic research has categorises schools as either private (fee-paying) or state-funded. However, UK university policy makers generally find that dividing schools into those that perform above and those that perform below the national average can bypass charges of ‘reverse discrimination’ against private schools.

Senior Lecturer in Higher Education King’s College London

This article was originally published in our AUA journal, Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education on 2 August 2016 and on the Taylor and Francis website. If your institution provides access to Taylor and Francis, you can receive updates about the journal directly by registering for a free account.

Bibliography:

Brint S.G. & Karabel J. (1989), The Diverted Dream: Community Colleges and the Promise of Educational Opportunity in America, 1900-1985, New York, Oxford University Press.

Chetwynd, P., (2011), A* at A-level as a predictor of Tripos performance: an initial analysis. University of Cambridge.

Chowdry, H., Crawford, C., Dearden, L. Goodman, A.,and Vignoles, A., (2013), Widening participation in higher education: analysis using linked administrative data,Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A – Statistics in Society, 176 p. 431.

Croxford, L. and Raffe, D., (2013), Differentiation and social segregation of UK higher education, 1996–2010, Oxford Review of Education, 39(2), p. 172.

DFE (2015), A level and other level 3 results (revised): 2013/14, London: Department for Education, Statistical First Release 03/2015 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/a-level-and-other-level-3- results-2013-to-2014-revised

Gallie, W. B. (1956). “Essentially contested concepts.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 56: 167-198.

Geoghegan, P.M. (2014) ‘The Irish Experiment: Undergraduate Admissions for the 21st Century’, International Perspectives on Higher Education Admission Policy: A Reader, 2014, p39 – 47.

HEFCE (2003), Schooling effects on higher education achievement HEFCE 2003/32. Available at: www.hefce.ac.uk/pubs/hefce/2003/03_32.htm

Hoare, A., and Johnston, R., (2011), Widening participation through admissions policy – a British case study of school and university performance, Studies in Higher Education, 36(1), p. 21.

Karabel, J. (2005). The chosen: the hidden history of admission and exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Boston, Houghton Mifflin.

King’s College (2015) Extended Medical Degree Programme. Available at: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/prospectus/undergraduate/emdp/details, accessed 5.09.2015.

Lasselle, L., (2014), School Grades, School Context and University Degree Performance: Evidence from an Elite Scottish Institution, Oxford Review of Education.

Machin, S (2006) Social Disadvantage and Education Experiences, OECD Social employment and migration working papers no. 32.

Moore, J, Mountford-Zimdars, A and Wiggans, J (2013) Contextualised admissions: examining the evidence Report of research into the evidence base for the use of contextual information and data in admissions of UK students to undergraduate courses in the UK, Report to Supporting Professionalism in Admissions August 2013

Mountford-Zimdars, A (2015) Contest and adjustment sponsorship in the selection ofelites: Re-visiting Turner’s mobility modes for England through an analysis of undergraduate admissions at Oxford University, Sociologie, issue 2, June 2015

Mountford Zimdars (2016) Meritocracy and the University: selective admission in England and the U.S.. Bloomsbury: London.

National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC) (2011) State of College Admission Report. NACAC. Available for purchase at: http://www.nacacnet.org/research/PublicationsResources/Marketplace/research/Pages/StateofCollegeAd mission.aspx

Nicholson, M. (2013) What Are Universities Selecting For? Conference Speech, Sutton Trust Advancing Access and Admissions Summit recording on, Nov 25 2013, available from the Sutton Trust website and from YouTube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sj8oS01pGT4.

Office for Fair Access (2013) How to produce an access agreement for 2014-15, available at: http://www.offa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/How-to-produce-an-access-agreement-for-2014- 15.pdf, accessed 05.09.2015.

Ogg, T., Zimdars, A., and Heath, A., (2009), Schooling effects on degree performance: a comparison of the predictive validity of aptitude testing and secondary school grades at Oxford University, British Educational Research Journal, 35(5), p. 781.

Parks, G., (2011), Academic Performance of Undergraduate Students at Cambridge by School /College Background. University of Cambridge.

Partington, R., Carroll, D., and Chetwynd, P.,(2011), Predictive Effectiveness of Metrics in Admission to the University of Cambridge, University of Cambridge. Available at:http://www.admin.cam.ac.uk/offices/admissions/research/a_levels.html

Quality Assurance Agency (2013), UK Quality Code for Higher

Education – Chapter B2: Recruitment, selection and admission to higher

education. Gloucester: Quality Assurance Agency. Available at:

http://www.qaa.ac.uk/publications/information-and-guidance/uk-quality-code-for-higher-educationchapter-b2-recruitment-selection-and-admission-to-higher-education#.VgUw1d9Viko,

accessed 05.09.2015.

Scottish Funding Council Guidance (2013). University Outcome Agreement Guidance

for AY 2014-15. Edinburgh: SFC. Available at: http://www.sfc.ac.uk/web/FILES/GuidanceOA1415/University_Outcome_Agreement_Guidance_2014-

15.pdf. Accessed 05.09.2015.

Stone, P (2014) Access to Higher Education by the Luck of the Draw in in Mountford-Zimdars, A, Sabbagh, D. and Post, D (eds)(2015) Fair Access to Higher Education: Global Perspectives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Supporting Professionalism in Admissions (SPA) (2012) Fair Admissions – what are the current issues in 2012? Outcomes from the SPA Fair Admissions Task and Finish Group – July 2012, available at: http://www.spa.ac.uk/documents/FairAdmissionsT&FGroup/Fair_Admissions_current_issues_Jul_2012.doc x, accessed 05.09.2015.

Supporting Professionalism in Admissions (SPA) (2014), Newsletter, autumn 2014, Cheltenham: SPA.

Supporting Professionalism in Admissions (SPA) (2013) Basket of contextual data and information available for HE providers via UCAS. Available at: http://www.spa.ac.uk/documents/ContextualData/UCASbasket_data_otherinformationviaUCAS.docx. Accessed 05.09.2015

Supporting Professionalism in Admissions (SPA) (2015), SPA’s Use of Contextualised Admissions Survey Report 2015 (with HEDIIP), Cheltenham: SPA.

Taylor, T., Rees, G., Sloan, L. and Davies, R.,(2013), Creating an inclusive higher education system? Progression and Outcomes of Students from Low Participation Neighbourhoods at a Welsh University, Contemporary Wales, 26, p.138.

Thomsen, JP (2012) Exploring the Heterogeneity of Class in Higher Education: Social and Cultural Differentiation in Danish University Programmes, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 33 (4), 2012, s. 565-585.

Turner, R.H. `Acceptance of Irregular Mobility in Britain and the United States’ (1966) 29 Sociometry 334±52.

University of Edinburgh (2015) Student Recruitment &

Admissions Briefing: contextual data in undergraduate admissions at the

University of Edinburgh.

Zimdars (2007) Challenges to meritocracy? A study of the social mechanisms in

student selection and attainment at the University of Oxford. DPhil. University

of Oxford.

0 comments on “Is contextualised admission the answer to the access challenge? AUA long reads”